In the thread started by Holy Cow on state licensure (my apology for contributing to the thread jack, HC), a poster not licensed in a PLSS state warbled out loud that U.S. Mineral Surveyors shamelessly bend senior line(s) through corners purported to be placed on the senior line(s) thereby creating angle points in the senior line. Unsurprisingly he said this in complete ignorance of the instructions that USMSs must comply with in the 2009 Manual. Mineral surveyors do no such thing (and never have) when conducting an official survey of mining claims.

The poster apparently read (or quote mined) a section in Chapter X of the 2009 Manual. Chapter X is titled, ÛÏSpecial Surveys and Mineral SurveysÛ. I will skip over the sections on ÛÏMine SurveysÛ (Secs. 10-86 through 10-93) since it deals with production verification, mine safety and reclamation of mineral and mineral-leased lands. And while IÛªm skipping sections, IÛªll also skip the sections on ÛÏMineral Segregation SurveysÛ (Secs. 10-94 through 10-100). In the past they were the exclusive purview of BLM Cadastral surveyors (akin to Independent Resurveys). I imagine that if the desire was strong enough a private surveyor could conduct a mineral segregation survey as long as it was done under the authority, special instructions and assignment instructions of the BLM Cadastral Chief.

The instructions to U.S. Mineral Surveyors on conducting official mineral surveys is covered in sections 10-101 through 10-207. The last paragraph of Sec. 10-107 does mention mineral segregation surveys stating their limited utility,

When necessary for the orderly administration of the Federal interest land, the BLM conducts a mineral segregation survey (section 10-94). However, such a mineral segregation survey is entirely distinct from a mineral survey, and no permanent rights confer upon the mining claimant as a result of the mineral segregation survey.

There is nothing in sections 10-101 through 10-207 that instruct or permit a U.S. Mineral Surveyor to bend a senior line through a junior corner. The specifics on surveying and reporting conflicts with prior official surveys is discussed in sections 10-144 through 10-151 under the topic heading, ÛÏConflictsÛ. Only the lines of prior official surveys in conflict with the patent survey are retraced. If, after a diligent search the necessary corners controlling a line in conflict cannot be found, they must be reestablished. Reestablishing lost corners of conflicting mineral surveys is a recent requirement for the mineral surveyor. In the past, if the mineral surveyor was unable to find the controlling corners, he would report the record position of the senior conflicting lines in his field notes. If the mineral survey was conducted after August 1904, the field notes will contain a section (either named "Report" or "Other Corner Descriptions"). This section describes the corners found and what lines are as previously reported. An example 1932 set of field notes for Sur. No. 20507 A&B states in the Other Corner Descriptions,

Sur. No. 3105 Becker Lode: Cors. Nos. 2, 3 and 4 could not be found. Cor. No. 1 is identical with Cor. No. 4 Sur. No. 3106 Colorado Springs lode, which was found fallen over but was reset in its original position. Lines shown as approved.

The plat for Sur. No. 20507 A&B shows corners 2, 3 and 4 in their record positions relative to the extant position of Cor. No. 1. It is imperative that the modern retracement/resurvey surveyor determine whether a senior line is based on its monumented position or its record position before using any ties to reestablish a lost mineral survey corner.

The only official mineral survey (that I know about) that was conducted under the 2009 ManualÛªs instructions was completed in 2012 in Arizona by Jim Crume. He wrote an article in Professional Surveyor describing the mineral survey, Field Notes: Revival of Mineral Surveys.

The next post will cover the sections, ÛÏResurveys-Mineral LandsÛ (Sections 10-208 through 10-229) and ÛÏSpecial CasesÛ (Sections 10-230 to 10-231). There are four topic headings in the resurveys section: ÛÏThe Nature of Dependent Resurveys of Mineral SurveysÛ (Secs. 10-208 to 10-212); ÛÏLost CornersÛ (Secs. 10-213 to 10-214); ÛÏPhysical Location and Title ConflictsÛ (Secs. 10-215 to 10-223); and ÛÏGaps and Overlaps Not of RecordÛ (Secs. 10-224 to 10-229). I hope that others (including those only licensed in Texas) will post their ideas on the last topic regarding when it may be appropriate to bend a senior line through a junior corner and particularly when it is not appropriate.

For completeness, a link to the 2009 Manual of Instructions

Before delving into mineral survey resurveys, I would like to list some differences between the rectangular PLSS and mineral surveys. I prepared this as an introduction to a mineral survey talk I gave on November 20, 2014 to a group of Federal land surveyors in Denver. Obviously, this is not a complete list, but it got the discussion started.

Characteristics of the Rectangular Survey System

- Global in design beginning with an Initial Point, Principal Meridian and Base Line;

- Land divisions are formed by a telescoping grid that is based on well-defined rules and procedures;

- The official survey is normally done prior to sale and before 1909, under contract with the U.S. Government;

- Most Township subdivision surveys are conducted under a single contract;

- Subdivision creates common boundaries between land parcels (in other words, the plan is that there are no overlaps or hiatuses);

- Subdivision does not normally create junior-senior relationships (e.g. a ÛÏregularÛ township subdivision);

- Bona fide rights as to location; and

- The concept of closing corners is well defined.

Characteristics of Mineral Surveys

- The initial possessory right to Mineral Lands is based on the discovery of a locatable mineral on ground open to mineral entry;

- The lode is determined by additional exploration and development;

- The mining claimant must sufficiently mark his claim so it is readily retraceable on the ground;

- Prior to patent, the claimant must do $100 of annual mining improvements to maintain his possessory right

- The mining claimant must employ and pay a U.S. [Deputy] Mineral Surveyor to conduct the official mineral survey after obtaining a survey order (the survey was approved by the U.S. Surveyor General, currently the Branch Cadastral Chief);

- For lode claims, bona fide rights to the subsurface mineral estate are fully preserved if the end lines are substantially parallel;

- The concept of closing corners is not well defined;

- Lode claims often overlap and junior-senior rights are the norm;

- Hiatuses and gaps between lode claims should be presumed to be the norm, not the exception;

- Mineral surveys are often tied to far distant, poorly established, shifting monuments, supposed to be corners of the public survey; and

- When retracing mineral surveys, thinking outside the box is to be encouraged!

Love it, Gene. Let's see how this proceeds.

The 2009 Manual is the first manual to include instructions on the resurvey of mineral lands. Prior to this the only GLO/BLM guidance on mineral survey resurveys was, ÛÏMineral Survey Procedures GuideÛ by John V. Meldrum, 1980. Resurveys are discussed in Chapter VI of the guide comprising a total of 4 pages (2 are diagrams). This guide was given to newly appointed U.S. Mineral Surveyors.

The introductory material is contained in the Chapter X topic, ÛÏThe Nature of Dependent Resurveys of Mineral SurveysÛ (10-208 to 10-212). It states the obvious that dependent resurveys of mining claims follow the same basic rules as dependent resurveys of the rectangular PLSS (see Chapters V, VI and VII). It then adds the wrinkle for lode mining claims that the endlines must be substantially parallel in order to preserve the bona fide rights to the subsurface mineral estate. The U.S. mining laws grant a mining claimant the right to follow the vein/lode at depth. In other words, the discovery of a locatable mineral in a mineralized vein grants the claimant to follow that vein at depth regardless of where it may "roam". If the mineralized vein is not vertical it will eventually extend beyond one of the side lines. This right is referred to as extralateral rights. Under the 1872 Mining Law, the portion of any lode or vein that apexes within the surface extents of a lode mining claim is owned by the claimant.

The introduction also includes the text of the Act of April 28, 1904 and an important DOI Land Decision, Sinnott v. Jewett (33LD91). The Act is only two paragraphs long and one might wonder why it was enacted. It states that when there is a discrepancy in the patent description and the monuments established by the U.S. Deputy Mineral Surveyor:

The said monuments shall at all times constitute the highest authority as to what land is patented, and in case of any conflict between the said monuments of such patented claims and the descriptions of said claims in the patents issued therefor the monuments on the ground shall govern, and erroneous or inconsistent descriptions or calls in the patent descriptions shall give way thereto.

I wonÛªt go into the legislative history of the Act, but suffice to say that Congress was perplexed as to why the legislation was sought since case law was abundantly clear on the subject. In the end, Congress was persuaded that the General Land Office was, ÛÏfoisting an evil upon the mining industryÛ that required a statutory remedy.

That brings up an interesting question for surveyors today. Is the Act merely a statutory restatement of case law, or does the Act provide special status to monuments established on mineral lands? For example, if the field notes call to a line of a prior official survey, are the monuments marking that senior line to be included in the "said monuments" that constitute what land is patented? If the answer is yes, then a monument of the junior mining claim that doesnÛªt reach the senior line (i.e. there is a gap between the junior and senior claims) shall be regarded as a closing corner. Or should the call to the senior line be covered by the text, "calls in the patent descriptions shall give way thereto" and, therefore, the junior corner shall not be treated as a closing corner.

The Sinnott v. Jewett Land Decision was promulgated by the Dept. of Interior Secretary on July 12, 1904 to comply with the Act of April 28, 1904. For those interested, I wrote a brief article in the August 2009 issue of Side Shots entited, The Sanctity of Monuments If anyone is interested in reading the full text of the decision and a compilation of the plats, field notes, MTPs and patents for the claims discussed in the Land Decision I can post a download link. The size of the Zip file is a mere 290 MB. In my opinion, this decision is the one Land Decision that surveyors should read. It is 11 pages long and repeatedly supports the principle that monuments control over course and distance!

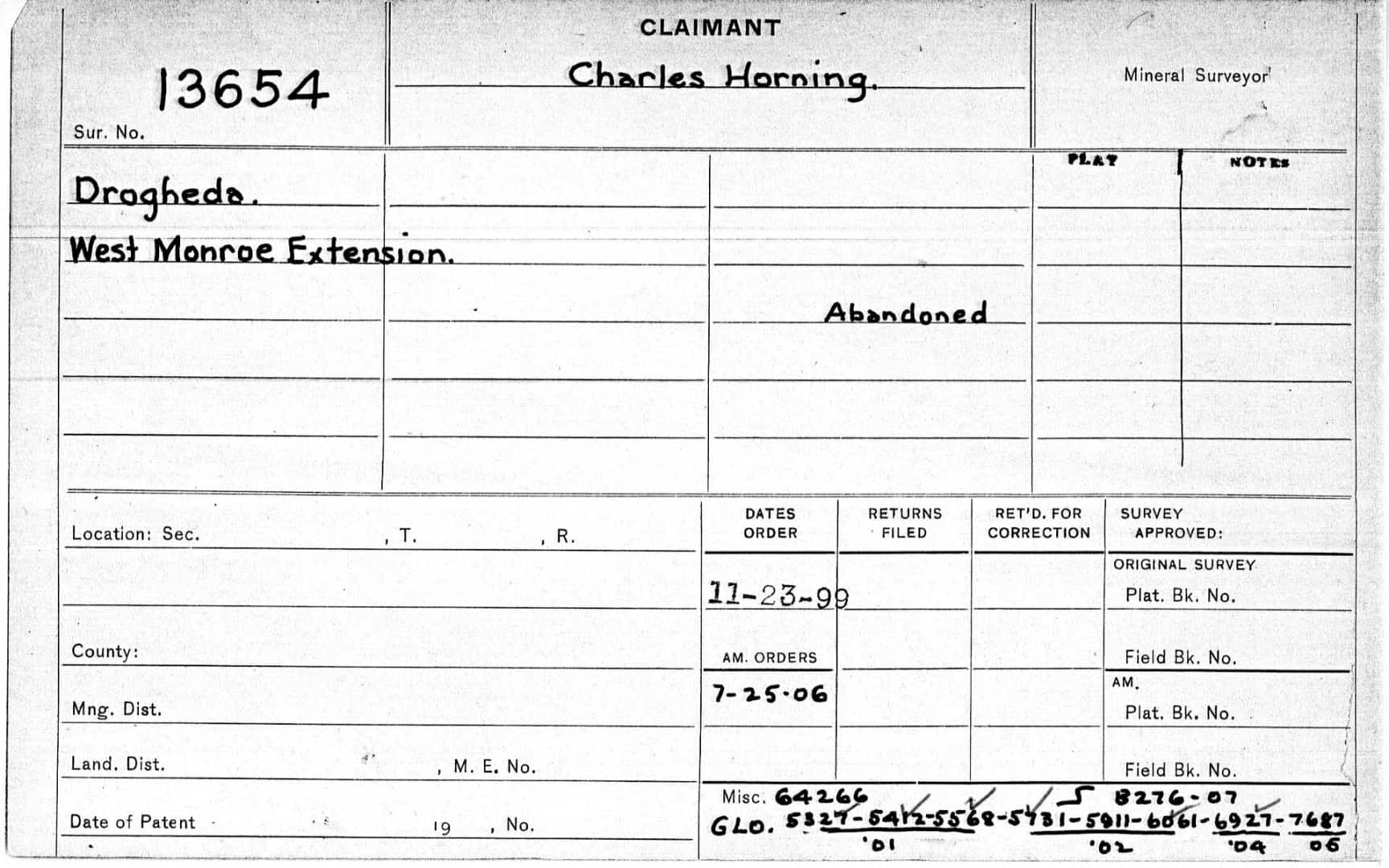

An aside: The Sinnott v. Jewett Land Decision covers the case where there is a conflict between claims on the ground, however there is no conflict in the record. The other case where there is no conflict on the ground, but there is a conflict shown in the record is covered in the Drogheda and West Monroe Extension Land Decision (33LD133) issued on August 11, 1904. That decision also includes revised language to Paragraph 147 of the U.S. Mining Regulations. In that case, the General Land Office insisted that the claimants of the Drogheda and West Monroe Extension claims get the owners of prior patented claims with erroneous descriptions to surrender their patents, conduct new mineral surveys to officially correct those errors and then apply for new patents. The claimants toiled for seven years to no avail and finally abandoned their claims!

The next topic under resurveys of mineral lands in Chapter X is, ÛÏLost CornersÛ. The first paragraph of Sec. 10-212 discusses how to reestablish lost lode claim corners.

There is no hard and fast rule for reestablishing lost corners of lode mining claims. The method should be selected that will give the best results, bearing in mind that end lines of lode claims should remain substantially parallel, if parallel by record. When the original surveys were made faithfully, the application of the principles of parallelism, record distances, record angular relationships, and record relationships between the claim and the workings on it, in combination with the presumption that the original intent was to be conformable with the statutes governing dimensions and area, should substantially meet the objectives stated above.

Here is a link to Chapter VI of MeldrumÛªs guide, which includes diagrams of various geometries of lode claims with lost corners and the default method of reestablishing those corners. I wish that the Manual would have included the two diagrams or at least add an addendum referencing the diagrams. For restoring lost corners of irregular mining claims (e.g. gulch placers and mill sites), ÛÏthe secondary methods of broken boundary adjustments covered in sections 7-53 and 7-54 should be considered.Û

For anyone keeping score, there is no instance in the sections discussed so far where the word, bend, bent or bending occurs, let alone any suggestion that senior lines should be deflected through junior corners.

After reading this (and thank you for the info, btw) I'm thinking Texas may have more in common with U.S. mining law than one might be led to think. Conditions where extralateral rights exist in mineral claims also probably exists in Texas surveying practice and surface claims. All one needs to do is find a surveyor that will place a new IP to make their client's property larger and extend these "extralateral" surface rights. But the shiny new pin must me placed in an obliterated and scattered pile of "Indian love rocks" to give credence that the surveyor located an up-until-now undiscovered corner of some ambiguous headright claim..

...that was no doubt originally set by Sammy Houston and Gordon Lightfoot. 😉

paden cash, post: 426730, member: 20 wrote: After reading this (and thank you for the info, btw) I'm thinking Texas may have more in common with U.S. mining law than one might be led to think. Conditions where extralateral rights exist in mineral claims also probably exists in Texas surveying practice and surface claims.

While not wishing to face the Wrath of Khan, I make the following lay observation regarding "mineral lands" in Texas. Since Texas was originally a Spanish colony, I would presume that any mineralized veins would not have extralateral rights. Spanish law did not recognize extralateral rights and lode claims in Mexico have no rights beyond the boundary marked on the surface. In other words, the extent of the claim is defined by vertical planes going through the end and side lines.

I will also presume that oil and gas plays constitute the great majority of "mineral lands" in Texas. For the western U.S. states and Alaska subject to U.S. mining laws, the Act of February 11, 1897 classified petroleum deposits as locatable minerals. The law specified that petroleum or other mineral oils were, "subject to the provisions governing placer mining claims". Therefore, there are no extralateral rights because they are placer claims. This makes sense as oil and gas plays are not located within mineralized veins, but rather geologic formations with sufficient porosity and structural geology to act as reservoirs to nearby source rocks (often marine shales).

On the subject of extralateral rights, it is not difficult to imagine that adjudicating those rights was often only profitable for the attorneys involved in the litigation. Some mining claim owners saw the wisdom of eliminating extralateral rights and the expense of litigation by invoking vertical side line agreements with their neighbors. Basically, they adopted the Spanish mining law regarding veins.

Continuing the discussion the next topic under the resurvey of mineral lands is, "Physical Location and Title Conflics" (Secs. 10-215 to 10-223). This topic covers the issue of seniority and what factors the resurveyor must evaluate in order to determine which patentee owns the area in conflict between two or more lode claims. The last paragraph in Section 10-215 provides a brief summary.

As a general rule, "first in time, first in right" will determine the priority of conflicting mining claims or sites. Determining the extent of rights to a mining claim or site typically depends on evidence gathered from prior sequential grants and surveys.

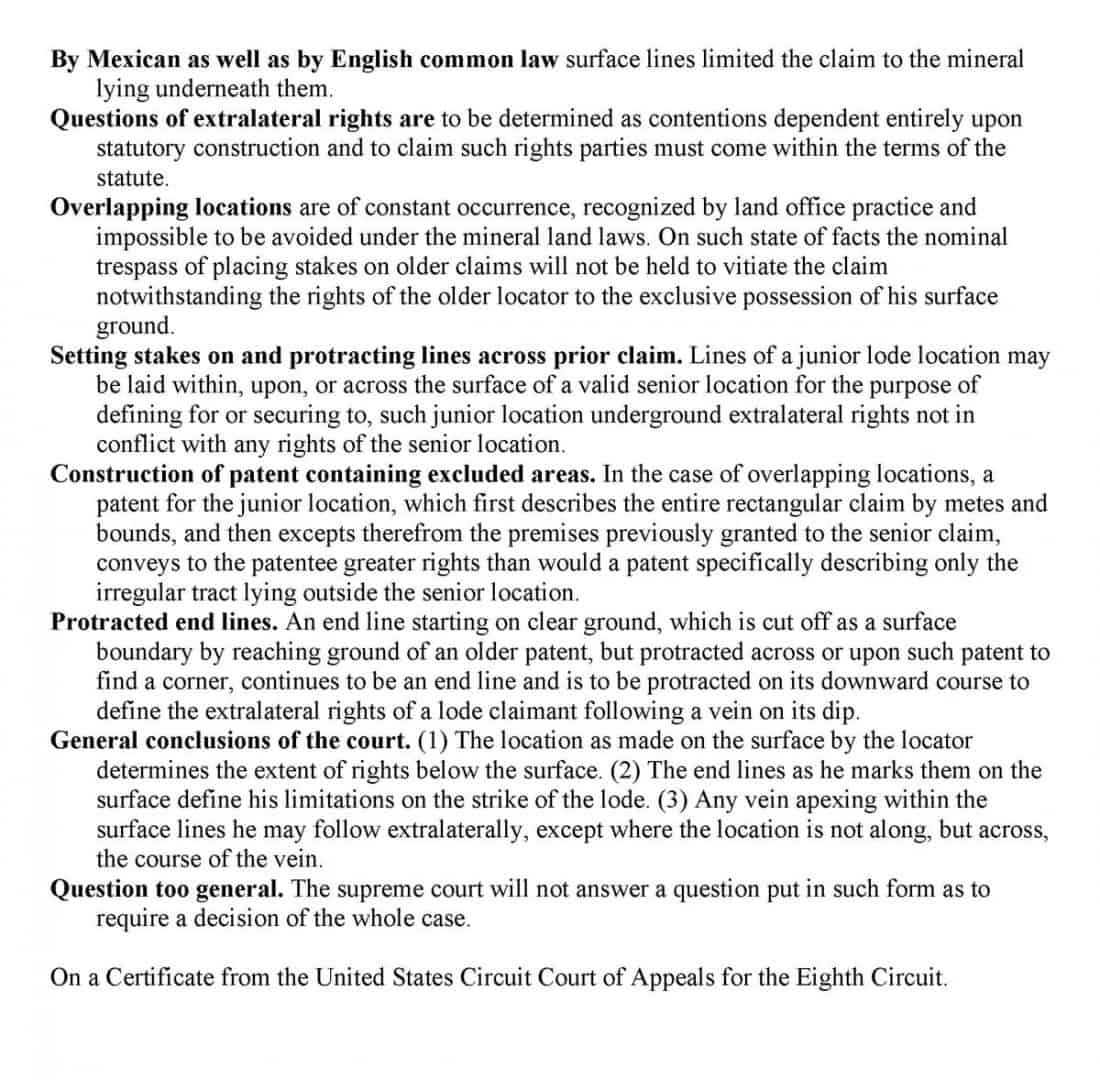

Before going any further, it is important to note that the mineral lands tenure system is unique, esp. with respect to lode mining claims. The claimant of a lode claim is attempting to acquire their full right under the mining laws to the subsurface mineral estate. In order to acquire their full right, the claim stakes set on the surface are often in conflict with other claims. It was customary in mining camps that a claimant was allowed to peaceably trespass upon and across the claim(s) of others to set his stakes. In support of this wild notion is the U.S. Supreme Court in its Del Monte Mining Co. vs. Last Chance Mining Co. (171 US 55), 1898. Below is an image of the head notes followed by four paragraphs extracted from the above linked decision that help explain the uniqueness of lode mining claims.

Again, the [lode claim] location upon the surface is not made with the view of getting benefits from the use of that surface. The purpose is to reach the vein which is hidden in the depths of the earth, and the location is made to measure rights beneath the surface. The area of surface is not the matter of moment. The thing of value is the hidden mineral below, and each locator ought to be entitled to make his location so as to reach as much of the unappropriated, and perhaps only partially discovered and traced, vein, as is possible.

Further, congress has not prescribed how the location shall be made. It has simply provided that it 'must be distinctly marked on the ground, so that its boundaries can be readily traced,' leaving the details, the manner of marking, to be settled by the regulations of each mining district. Whether such location shall be made by stone posts at the four corners, or by simply wooden stakes, or how many such posts or stakes shall be placed along the sides and ends of the location, or what other matter of detail must be pursued in order to perfect a location, is left to the varying judgments of the mining districts. Such locations, such markings on the ground, are not always made by experienced surveyors. Indeed, as a rule, it has been and was to be expected that such locations and markings would be made by the miners themselves,ÛÓmen inexperienced in the matter of surveying,ÛÓand so, in the nature of things, there must frequently be disputes as to whether any particular location was sufficiently and distinctly marked on the surface of the ground. Especially is this true in localities where the ground is wooded or broken. In such localities the posts, stakes, or other particular marks required by the rules and regulations of the mining district may be placed in and upon the ground, and yet, owing to the fact that it is densely wooded, or that it is very broken, such marks may not be perceived by the new locator, and his own location marked on the ground in ignorance of the existence of any prior claim. And in all places posts, stakes, or other monuments, although sufficient at first, and clearly visible, may be destroyed or removed, and nothing remain to indicate the boundaries of the prior location. Further, when any valuable vein has been discovered, naturally many locators hurry to seek by early locations to obtain some part of that vein, or to discover and appropriate other veins in that vicinity. Experience has shown that around any new discovery there quickly grows up what is called a 'mining camp,' and the contiguous territory is prospected, and locations are made in every direction. In the haste of such locations, the eagerness to get a prior right to a portion of what is supposed to be a valuable vein, it is not strange that many conflicting locations are made; and, indeed, in every mining camp where large discoveries have been made locations in fact overlap each other again and again. McEvoy v. Hyman, 25 Fed. 596-600. This confusion and conflict is something which must have been expected, foreseen; something which, in the nature of things, would happen, and the legislation of congress must be interpreted in the light of such foreseen contingencies.

Still again, while a location is required by the statute to be plainly marked on the surface of the ground, it is also provided in section 2324 that, upon a failure to comply with certain named conditions, the claim or mine shall be open to relocation. Now, although a locator finds distinctly marked on the surface a location, it does not necessarily follow therefrom that the location is still valid and subsisting. On the contrary, the ground may be entirely free for him to make a location upon. The statute does not provide, and it cannot be contemplated, that he is to wait until by judicial proceedings it has become established that the prior location is invalid, or has failed, before he may make a location. He ought to be at liberty to make his location at once, and thereafter, in the manner provided in the statute, litigate, if necessary, the validity of the other as well as that of his own location.

Congress has, in terms, provided for the settlement of disputes and conflicts, for by section 2325, when a locator makes application for a patent (thus seeking to have a final determination by the land department of his title), he is required to make publication and give notice so as to enable any one disputing his claim to the entire ground within his location to know what he is seeking, and any party disputing his right to all or any part of the location may institute adverse proceedings. Then, by section 2326, proceedings are to be commenced in some appropriate court, and the decision of that court determines the relative rights of the parties. And the party who, by that judgment, is shown to be 'entitled to the possession of the claim, or any portion thereof,' may present a certified copy of the judgment roll to the proper land officers and obtain a patent 'for the claim, or such portion thereof, as the applicant shall appear, from the decision of the court, to rightfully possess.' And that the claim may be found to belong to different persons, and that the right of each to a portion may be adjudicated, is shown by a subsequent sentence in that same section, which provides that, 'if it appears from a decision of the court that several parties are entitled to separate and different portions of the claim, each party may pay for his portion of the claim, * * * and patents shall issue to the several parties according to their respective rights.' So it distinctly appears that, notwithstanding the provision in reference to the rights of the locators to the possession of the surface ground within their locations, it was perceived that locations would overlap, that conflicts would arise, and a method is provided for the adjustment of such disputes. And this, too, it must be borne in mind is a statutory provision for the final determination, and is supplementary to that right to enforce temporary possession, which, in accordance with the rules and regulations of mining districts, has always been recognized.

The last post was too long to also include a discussion regarding how the resurveyor should evaluate the seniority of mining claims. After consulting with other surveyors on this topic numerous times, I decided it was worthwhile to prepare a white paper. I included the paper as part of my course materials for a talk I gave back in February at the PLSC conference. I attached a PDF file of it to this post. It is certainly not an exhaustive list of the situations that a surveyor may run across. I would appreciate any criticisms or comments as it is a draft document.

An aside: In the paper I discuss conflicts with unpatented claims and the concept of casting off any excess in the dimensions of the unpatented claims (See the figure for the Two Point claim). I had previously skipped over the sections in Chapter X dealing with mineral segregation surveys (sections 10-94 to 10-100). There is information in those sections that deal with how one might cast off the excess in a claim that exceeds the statutory limits of 1500 feet along the lode and up to 300 feet each side of the lode. Additional information is included in sections 10-116, 10-131 and 10-197 which are part of the instructions to U.S. Mineral Surveyors conducting a mineral patent application survey.

Keep learning neat stuff every day by hanging around this particular water cooler. Thanks, Gene.

Thanks Gene - I'm adding this to the very narrow section of my library dealing with mineral land surveying. Mining claims are extraordinarily interesting beasts!

Thanks for the great posts Gene.

As an aside, there may be some that have confusion with the term Mineral Surveyor.

There are different classes of minerals in the Federal system such as locatable, saleable, leasable. For locatable minerals-lode claims, placer claims it's necessary to hire a Mineral Surveyor, but for the vast majority of minerals under federal control it isn't.

These types of minerals can also be mixed.

Some areas have federal minerals that have come to patent over the top of existing private patented surface and even with existing private minerals, which of course causes split estate with two different private mineral owners, a private surface owner and federal minerals, it can be very confusing.

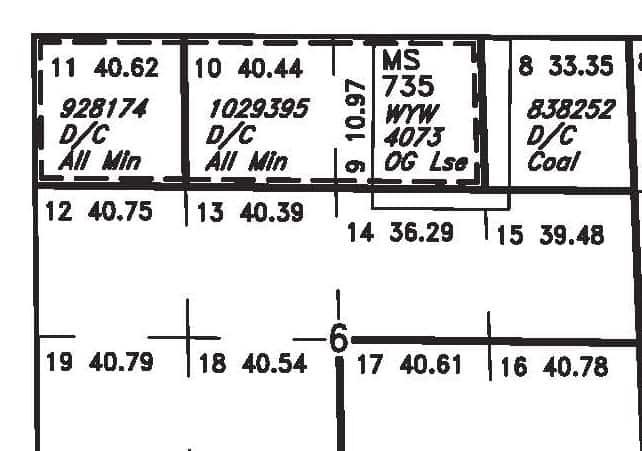

Here is an example of a locatable mineral "over" the top of private surface ownership which owns all of Sec 6. MS 735 slops across Lot 1 (private surface, private oil and gas), Lot 2 (private surface), the S2NE4 (private surface, private oil and gas), I presume that MS735 is still Federal coal, that is unclear on this plat, but it is clear that Lot 9 and the rest of the original Lot 2 have been included in a Federal OG lease which is separate from the mineral surveyed for in MS 735:

As I understand it the Mineral Survey created a patent to the mineral but not the land.

For all the mineral classes inside Section 6 a registered land surveyor can survey them with the exception of the locatable minerals which require a Mineral Surveyor.

Gene Kooper, post: 426726, member: 9850 wrote:

An aside: The Sinnott v. Jewett Land Decision covers the case where there is a conflict between claims on the ground, however there is no conflict in the record. The other case where there is no conflict on the ground, but there is a conflict shown in the record is covered in the Drogheda and West Monroe Extension Land Decision (33LD133) issued on August 11, 1904. That decision also includes revised language to Paragraph 147 of the U.S. Mining Regulations. In that case, the General Land Office insisted that the claimants of the Drogheda and West Monroe Extension claims get the owners of prior patented claims with erroneous descriptions to surrender their patents, conduct new mineral surveys to officially correct those errors and then apply for new patents. The claimants toiled for seven years to no avail and finally abandoned their claims!

First... Great series of posts Gene.

Second, (for those who wish to view the actual Land Decisions), Drogheda and West Monroe Extension Land Decision (33LD133) issued on August 11, 1904., is 33LD183 not 33LD133.

Keep it coming Gene.

Loyal

Loyal, post: 426810, member: 228 wrote: Second, (for those who wish to view the actual Land Decisions), Drogheda and West Monroe Extension Land Decision (33LD133) issued on August 11, 1904., is 33LD183 not 33LD133.

Keep it coming Gene.

Loyal

Thanks for fixing my typo, Loyal. I blame weak eyes for seeing "133" when it is clearly "183". Before I get to bending lines, I'll add my research and the Land Decision for the Drogheda and West Monroe Extension lodes.

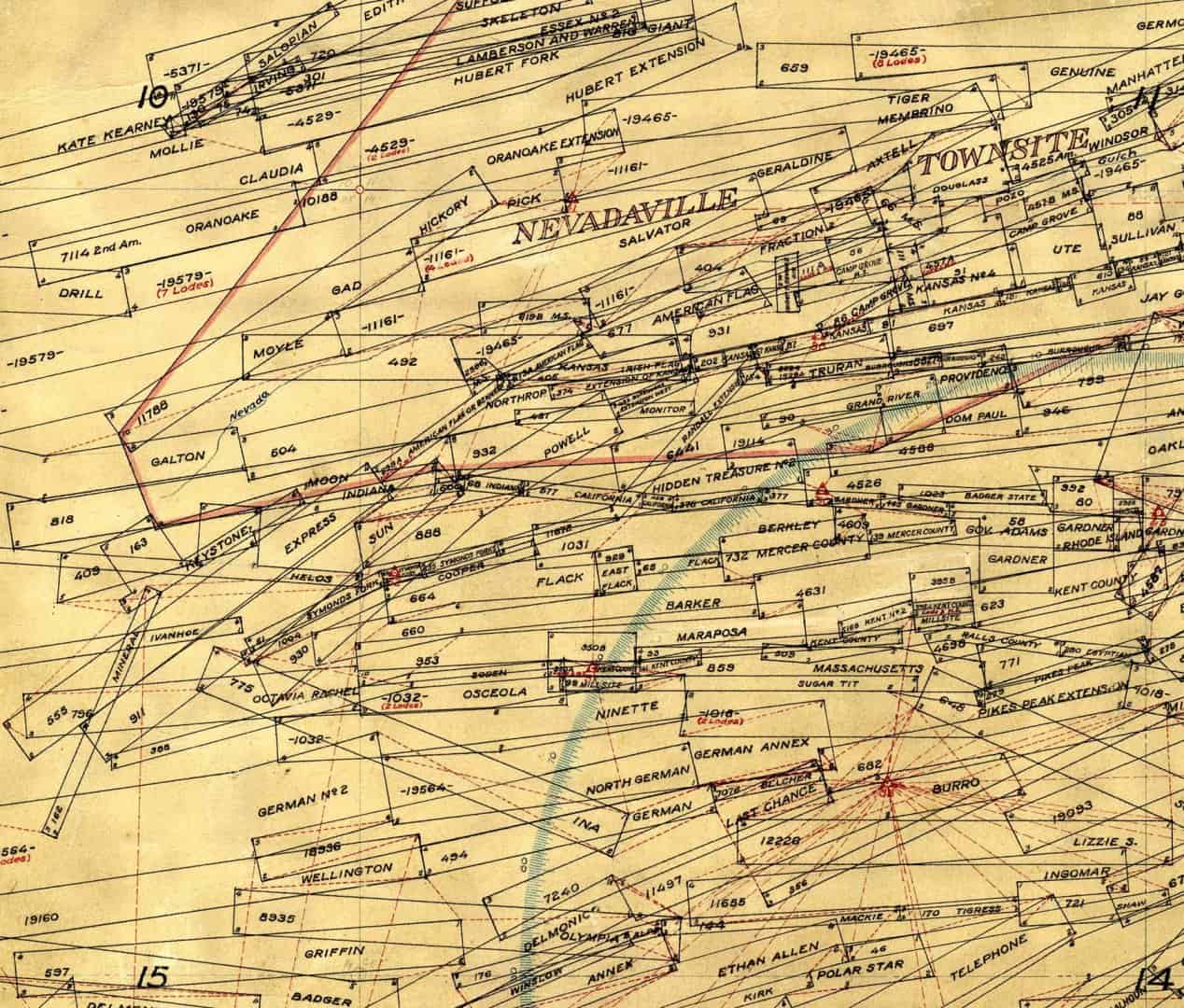

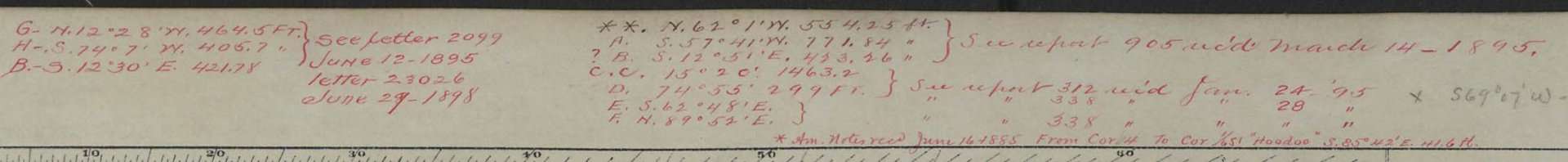

Sometimes a picture is helpful. Neither the Drogheda Lode nor the West Monroe Extension Lode are shown on the connected sheet. This is because only approved mineral surveys are shown on connected sheets. My best notion of their locations are somewhere in the vicinity of the Indiana lodes (north of the Cooper Lode) which are along the southern boundary of the Nevadaville Townsite (west center of the image). Nevadaville is west of Central City, Colorado.

Portion of the connected sheet - NW-1/4 of Sec. 14, T. 3 S., R. 73 W.

All of the mineral surveys shown in the above connected sheet have "official" ties of 7500 to 10000 ft. to corners on the east Range Line of T. 3 S., R. 73 W.

Index card for Sur. No. 13654. The two claims were abandoned. The "Misc." section in the lower right of the card lists 8 GLO Departmental letters that were sent from the GLO Commissioner's office to the U.S. Surveyor General for Colorado. The four-digit numbers refers to an index number assigned to each letter by the SG office up receipt. The two digit numbers represent the years sent. (The index cards are housed at the BLM Public Room.)

I attached a copy of the Drogheda Land Decision along with the last GLO letter (No. 8276 sent in 1907) as a PDF file for those interested in the bureaucratic details. The mineral survey order was issued on Nov. 23, 1899 and finally on May 22, 1907 the Surveyor General was advised as follows:

After the Rocky Mountain National Bank came into possession of the above named properties (Drogheda and West Monroe (sic) lodes, Survey 13644 (sic) it was found that there was too little vacant ground available in the surveys to warrant going forward with the application for patent, hence the same is abandoned.

In other words the bank likely obtained the possessory rights to the two claims after Charles Horning defaulted on a loan (after he spent nearly 7 fruitless years to get the mineral survey approved!)

Before discussing the topic ÛÏGaps and Overlaps Not of RecordÛ, I want to cover the last topic in Chapter X, ÛÏSpecial CasesÛ (Secs. 10-230 and 10-231). In my opinion, Section 10-230 is key to applying the resurvey rules and instructions laid out in Chapter X. None of the rules and instructions should be strictly adhered to, but rather, ÛÏexperience, thoroughness and good judgment are indispensable for the successful retracement and recover of any surveyÛ?.Û and therefore, should temper the rules.

It is an axiom among experienced cadastral and mineral surveyors that the true location of the original lines and corners can be restored, if the original survey was made faithfully, and was supported by a reasonably good field-note record. That is the condition for which the basic principles have been outlined, and for which the rules have been laid down. The rules cannot be elaborated to reconstruct a grossly erroneous survey or a survey having fictitious field notes.

I want to comment on the last part of the above quote. During the time period from July 1899 to August 1904 fictitious field notes were the rule rather than the exception for mineral surveys showing a conflict with a prior official survey. The July 1899 beginning date only applies to Colorado. In other western states, the beginning date was likely some time in 1900. The fiction does not lie with the position of the mining claim being surveyed, but with the positions shown of prior official surveys. By way of illustration, from The Annual Report of the Commissioner of the General Land OfficeÛ, 1901 is this excerpt from the annual report prepared by Edward H. Anderson, Utah Surveyor General dated, June 30, 1901 (SG Anderson also included the below text in his 1902 and 1903 reports).

The Department of Interior holds that courses & distances once incorporated into a patent must be recognized in all subsequent conflicting & adjacent surveys, notwithstanding actual conditions on the ground to the contrary. This means a perpetuation of the error, if any exist, in the former patented survey, and the deputy who makes the latter survey is compelled to falsify his returns to conform to such error. The courts hold that the monuments and markings on the ground govern.

The manner in which the U.S. Deputy Mineral Surveyor was forced to report the conflicts with prior official surveys followed this general form. He made connections from his survey to one or more corners of the PLSS (in certain situations it was to a U.S. Mineral Monument). Using his connection(s) to those corners, the deputy then played a childÛªs game. He took the record position of the prior official survey(s) and played ÛÏpin the tail on the donkeyÛ.

In other words, he started with his surveyed position of the PLSS corner and then computed the position of the senior claim from the surveyed control corner based solely on the record of the prior survey. Where the computed senior survey draped across his survey is where he described it to be in his field notes and on his preliminary plat (i.e. falsified his returns). The original monuments of the senior survey(s) were ignored. At least in Colorado this was not a rare occurrence as slightly over 4000 mineral survey orders were issued during the 5+ years that the policy was enforced by the GLO. The previously discussed Act of April 28, 1904 overturned this policy and required the General Land Office to promulgate new rules and policy via the Sinnott v. Jewett and Drogheda and West Monroe Extension land decisions.

Section 10-231 is mainly directed at the BLM Cadastral surveyor engaged in an official dependent resurvey, but this sentence can equally apply to private surveyors.

When the surveyor encounters unusual situations, or finds it difficult to apply the normal rules for good faith location and substantially as approved or for the restoration of lost corners, the surveyor will report the facts to the proper administrative office.

Almost every mineral survey has the potential of bordering the Public Lands. Loyal is fond of calling those ÛÏImperial EntanglementsÛ. The proper ÛÏadministrative officeÛ for private surveyors to contact would be the state Branch Cadastral Chief. The Branch Cadastral Chief is the person delegated (through the authority assigned by Congress to the Dept. of Interior Secretary) to determine the extents of the Public Lands in the state(s) they are assigned.

The "Binger Period" (1899-1904) is a HUGE Bear trap for the average Land Surveyor, Title Weenies, and many others who don't know/understand the History of Mineral Surveys in General. There are quite a number of other nuances unique to Mineral Surveys that can bite the unprepared on the butt. I have seen some real whoopers recently that are a direct result of Land Surveyors who should NOT have got involved in retracing Mineral Surveys that they are UNQUALIFIED to retrace. In fact, they should keep their damn Penny Loafers on the pavement of the Salt Lake Valley!

Oh yeah...GET OF MY LAWN.

Loyal

Loyal,

I brought up that GLO policy while discussing the "Special Cases'' expressly for the reason you stated above (NO, not GET OFF MY LAWN). The 2009 Manual does not make any mention of the "Binger" period, which is named after the Hon. Commissioner of the General Land Office, Mr. Binger Hermann who served from 1897 to 1903. The Act of April 28, 1904 and the Sinnott v. Jewett Land Decision are mentioned under "Resurveys", but no mention is made for why those occurred or what they "cured".

Since the penultimate section in Chapter X mentions "fictitious field notes", I took the opportunity to insert the "Binger" policy there. I wish the text in the 2009 Manual would have adopted and even expanded on what is in Chapter VI of Meldrum's guide. Section 10-214 contains no context and IMHO reads like gobblygook. If taken literally, pretty much every mineral survey before August 1904 (when the "Report" section describing other found corner monuments was added) is suspect regarding ties to other mineral surveys. Or does it make sense to you (without knowing the term, to binger?).

10-214. Caution should be exercised in the use of any ties to or from adjoining surveys when the descriptions for the conflicting claim corners, PLSS corners, or mineral monuments are not mentioned in the field notes memorandum and may in fact have only been calculated and not surveyed on the ground. Such calculated ties, as a rule, should not be used.

I am still awestruck that a U.S. Surveyor General would state in his official annual report that the deputies under his charge were forced to "falsify their returns". Their only other choice was to resign their appointments. Writings of the time mentioned that many did just that.

Part 1

The last topic under resurveys of mineral lands in Chapter X is, ÛÏGaps and OverlapsÛ Not of Record (Secs. 10-224 through 10-229). The Manual places quotes around Gaps and Overlaps to qualify their normal meaning. After plotting up the monument positions in a CAD program and zooming in to the line one may see a gap or overlap, but they are not of record and, therefore only technical gaps or overlaps. Note that the topic title is NOT ÛÏBending Senior Lines Through Junior CornersÛ! In fact, neither term is used in sections 10-224 through 10-229. The term ÛÏintermediate monumentÛ is instead used, so the situation can be either a junior monument on a senior line or a senior monument on a junior line!

The introductory section (Sec. 10-224) states that the rules included in the sections that follow apply to situations where, ÛÏthe record is clear that monuments were set to mark corners common to two claimsÛ. For situations where that is the case, ÛÏÛ?.the presumption is that the claim line as marked is common to the two claims.Û Even with todayÛªs modern equipment it is not possible to place an intermediate monument exactly on a straight line so, ÛÏslight variations in direction or distance are unavoidable and acceptable.Û During the field survey the offset of the intermediate monument from the straight line as marked is noted. The field conditions are analyzed to determine, ÛÏwhether the line is common to the claims or the error is so gross as to impair a legal right as to position so that the claims were never contiguous.Û So, the rule whereby a line will be deflected through an intermediate monument only applies to a specific set of conditions.

Section 10-225 describes the conditions that shall be met before the bending begins.

When the relationship between the monuments is substantially as approved, and there is no evidence of fraud, mistake, or gross error, the line running though the intermediate monument, as measured, will be returned as common to the claims.

When determining whether the conditions found during the retracement are substantially as approved, the surveyor shall be guided by law, rules, official policy, effect on extralateral rights, and survey principles thereof.

The threshold of ÛÏgross error or fraudÛ has often been evaluated before corrective actions were taken. For example, after a dependent resurvey has been approved by the BLM and the comment period has elapsed, a protester of the resurvey must prove by a preponderance of the evidence that the resurvey meets the gross error or fraud standard. One of the more entertaining definitions of gross error that IÛªve seen is, ÛÏI know it when I see it!Û

Section 10-225 also includes the term ÛÏmistakeÛ as an additional condition to determine if it is appropriate to bend lines. I am not aware of any published IBLA cases where the term ÛÏmistakeÛ was defined, nor the conditions where it has be applied in the context of Section 10-224. So, what should the resurveyor take as the definition of ÛÏmistakeÛ as used in Section 10-225? Should mistake be regarded as a material error in the establishment of the intermediate monument by the U.S. [Deputy] Mineral Surveyor (senior line, junior corner situation)? Or a material error in the positioning of one or both of the monuments marking the line (junior line, senior corner situation)?

From my reading of old manuals of instructions for the mineral lands the term material error is equivalent to not being substantially as approved. The 1886 manual of instructions for mineral surveyors for the district of Colorado is the first instance that I am aware where the deputy was required to report any material errors. The deputy was required to submit a separate letter report with his returns. I suppose that one could look through the historical records and obtain an empirical notion of what constituted a material error in course and/or distance. However, the letter reports (at least in Colorado) appear to have been destroyed. The evidence of the reported material errors that does exist are notations (usually in red ink) on the top margin of the mineral survey plat of the survey having the alleged error(s). As an example, below is an image of the top margin of Mount Yale Placer, Sur. No. 3976 and a link to the plat on the GLO Records web site. As I mentioned earlier, each letter report was submitted with the survey returns, so each letter number corresponds to a mineral survey that noted material errors somewhere in the placer boundary.

A mistake may also be regarded by some as any error that exceeds the maximum closure tolerance for mineral surveys of 1:2000. The 2009 Manual changed the closure tolerance to 1:4000. The question then becomes just how does one calculate the maximum permissible error based on a closure tolerance. I suppose that one could take the record boundary perimeter and compute the maximum permissible closure error. For example, a simple rectangle with dimensions of 1500Ûª by 600Ûª has a perimeter of 4200 feet. Applying the 1:2000 closure tolerance would give a maximum error in the offset of 2.1 feet. Another definition of mistake applicable to section 10-225 might be where, "the error is so gross as to impair a legal right as to position so that the claims were never contiguous". I take the meaning of gross in this context to be "large", and not the same as "gross error". IÛªm sure there are any number of notions of what should constitute a mistake as used in section 10-225.

So, how close must the intermediate corner be to the marked line for bending to occur?

[USER=9850]@Gene Kooper[/USER]

Maps such as that always amaze me.

In 1984 I made a mineral interest map of the town of Bloomburg, Texas and the result was the size of a bed sheet and took a decoder ring to understand.

It was all due to the fact there was a processing plant north of there that was being refitted and placed into action to suck whatever it could out of the ground and a flurry of leases were being pooled.

Part 2 (It took some time to prepare this and I reached the character limit for a post, so Sec. 10-229 and other information is included in Part 3)

Sections 10-226 through 10-229 in the 2009 Manual are directed at surveyors conducting official resurveys, that is, the surveyor has Federal survey authority. The beginning of section 10-226 reiterates that the authority is granted to the Secretary of Interior by Congress (43 U.S.C. 772). The authorized surveyor is delegated the authority to determine ??the boundary location of lands within Federal province.?

The questions I have regarding Sec. 10-226 are regarding when a surveyor with federal survey authority can reject a monument found to be ??in its original position, but not at its record position? and whether the monuments were set in the original mineral survey or a prior dependent resurvey of the mineral survey. My questions relate to the following extract:

Sec. 10-226, third paragraph:

The intermediate monument in its original position, but not at its record position, was approved even though based on false assumptions. Unless set aside by direct proceedings, such a decision of approval, even with the technical error, will bind the Government except when fraud, mistake, or gross error can be proven. Questions respecting position are to be determined by the conditions existing at the time when all requirements necessary to approve the survey had been complied with, and no subsequent change in such conditions can affect this physical location." (underlining is my emphasis)

A narrow reading of this paragraph indicates that this applies to original surveys that were approved, but should not apply to surveys where a patent has been issued and is still outstanding. I base this in part on the general statement that, ??a patent to a mining claim cannot be vacated or limited by the government officers themselves as their power over the land is ended when the patent is issued and placed on the records of the department" (Steele v. Smelting Co. 1882; 1 Sup. Ct. 389, 106 U.S. 447, 454, 27 L. Ed. 226). The patent must be vacated or annulled by direct proceedings (i.e. by a court of competent jurisdiction) in which fraud, mistake or gross error were proven by clear and convincing evidence. Only after such judgment may a surveyor conducting an official resurvey reject a monument established by an approved original mineral survey.

In my research I found a reference in Lindley on Mines, 1914 (?? 784. Patents - How Vacated; see attachment below) that placed limits on government challenges to land patents (page 1026 of Lindley).

By act of congress, approved March 3, 1891 (23 Stats. at Large 1093, ?? 8) it was enacted that suits by the United States to vacate and annul any patent theretofore issued should only be brought within five years from the passage of this act, and that suits to vacate and annul patents thereafter issued shall only brought within six years after the date of the issuance of the patent.

This act specifically amended the Timber Culture Act, but courts have ruled that it is also applicable to patents issued for mineral lands (Peabody Gold M. Co. v. Gold Hill M. Co., 106 Fed. 241). Lindley continues on page 1927 with:

It has been said that the object of the statute is to extinguish any right the government may have had in the land and vest a perfect legal title in the adverse holder after six years from the date of the patent, regardless of any mistake or error in the land department, or fraud or imposition of the patentee (United States v. Smith, 181 Fed. 545, 554). Other courts of equal dignity, however, maintain the doctrine that the statute does not commence to run until the fraud is discovered (United States v. Exploration Co., 203 Fed 387, Exploration Co., Ltd. v. United States 247 U.S. 435 (1918)).

The Act of April 28, 1904 (30 USC 34) is quite clear that the officially established monuments shall constitute the highest authority of which lands have been patented (see attachment below). The Act does not qualify that with "except when gross error, mistake or fraud can be shown". My interpretation of the above indicates that the Federal government would have to vacate the patent before a surveyor conducting an official resurvey would have authority to reject a monument of a patented mining claim under the instructions in Sec. 10-226.

I base my opinion in part on the last paragraph of Sec. 10-226 which states, "Reviewing courts will hold unlawful and set aside agency action, findings, and conclusions found to be arbitrary, capricious, an abuse of discretion, or otherwise not in accordance with law or in excess of statutory authority." (underlining is my emphasis)

One other possible interpretation of the third paragraph of Sec. 10-226 is if the term ??official survey? refers to prior official dependent resurveys of mining claims. In that case, any monuments established as part of the resurvey can be rejected if sufficient evidence determines that gross error, mistake or fraud occurred.

Section 10-227 states that the, ??United States retains the power to make corrective adjustments for prior erroneous survey monument positions, and the BLM has the burden of proving that a monument position of an official survey is erroneous? and that the, ??courts have emphasized they are very reluctant to overturn long-established and accepted boundaries, as is Congress??.once the physical position of a mining claim is fixed on the basis of an official survey.?

Once again, my understanding is that the Federal government has the authority to change or "make corrective adjustments" of prior approved surveys, but once a patent has been issued they have no jurisdiction unless and until they successfully vacate the patent based on whatever a court of competent jurisdiction determines is appropriate. However, this section would be directly applicable to monuments reestablished during prior resurveys.

To answer my question in a previous post, I am of the opinion that the Act of April 28, 1904 did assign a special status to mineral survey monuments. If a monument to a patented mining claim is found at the position it was "officially established upon the ground", the surveyor conducting an official resurvey has no authority to reject it unless and until the patent has been vacated or annulled. The U.S. [Deputy] Mineral Surveyor was required to reference, ??natural objects or permanent monuments as will perpetuate and fix the locus thereof? to fully identify the mining premises. As such, the mineral surveyor was instructed to establish accessories if practicable. One of the more important tasks of a surveyor conducting a retracement/resurvey of a mineral survey is a diligent search for the original accessories.

Section 10-228 quotes from 43 U.S.C. 772 ?? Resurveys or retracements to mark boundaries of undisposed lands, ??that no such resurvey or retracement will impair any bona fide rights or claims of any claimant, entryman, or owner of lands affected by such resurveys.? I believe the second sentence of this section states succinctly the reasoning behind the instructions in the Manual dealing with gaps and overlaps not of record when conducting a resurvey.

In cases where gaps or overlaps are not in the official record, the subsequent identification of long narrow strips and isolated small plots of land by rigorous application of modern technology during a mineral dependent resurvey or retracement will ordinarily not be accepted as defining survey and title lines. (underlining is my emphasis)