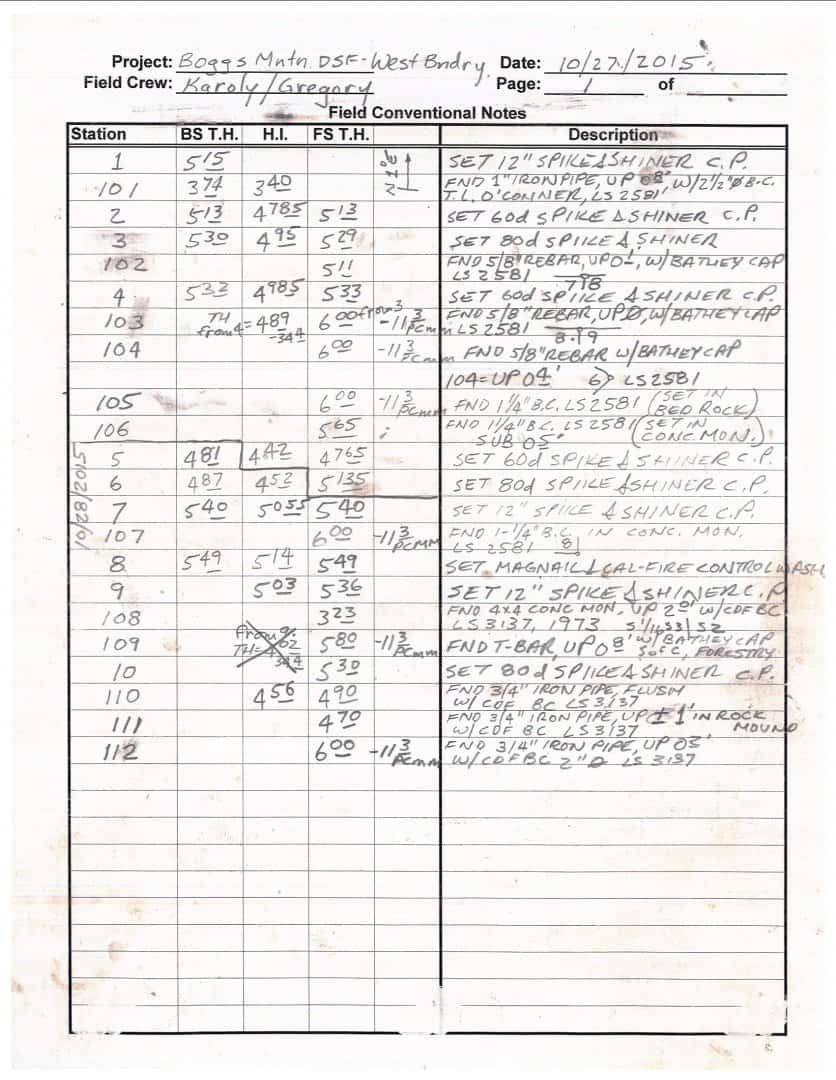

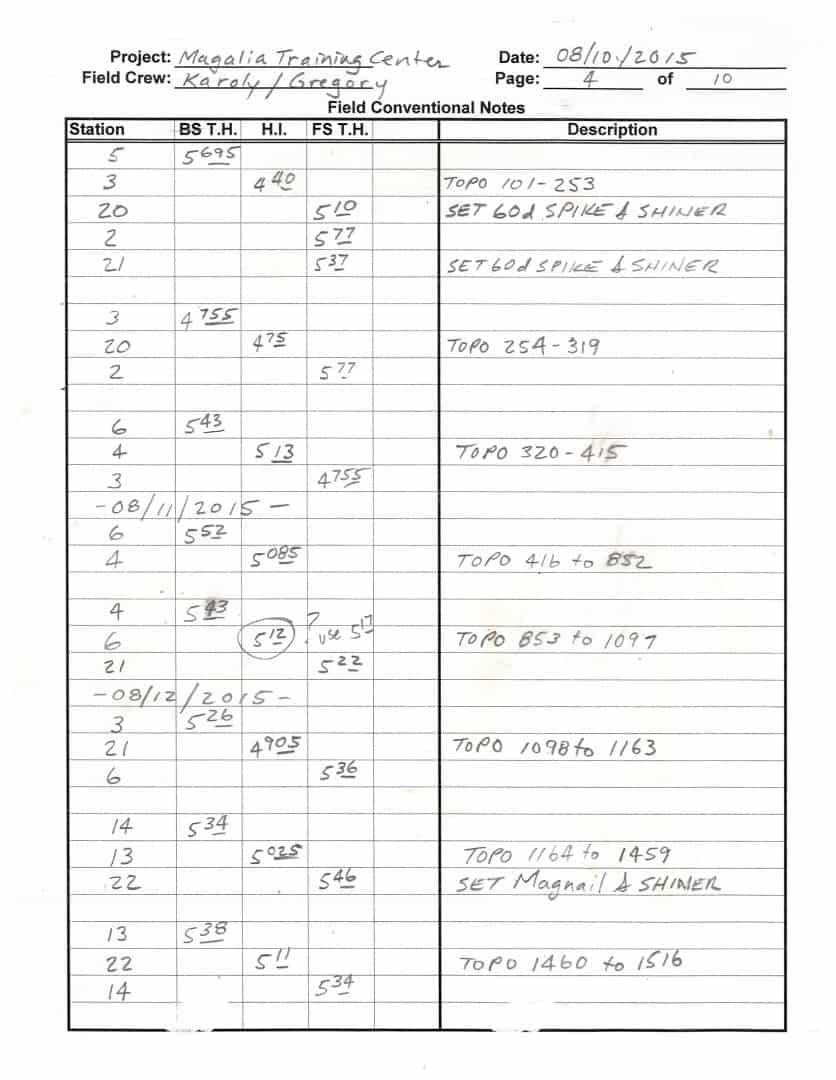

All of our field notes include the following

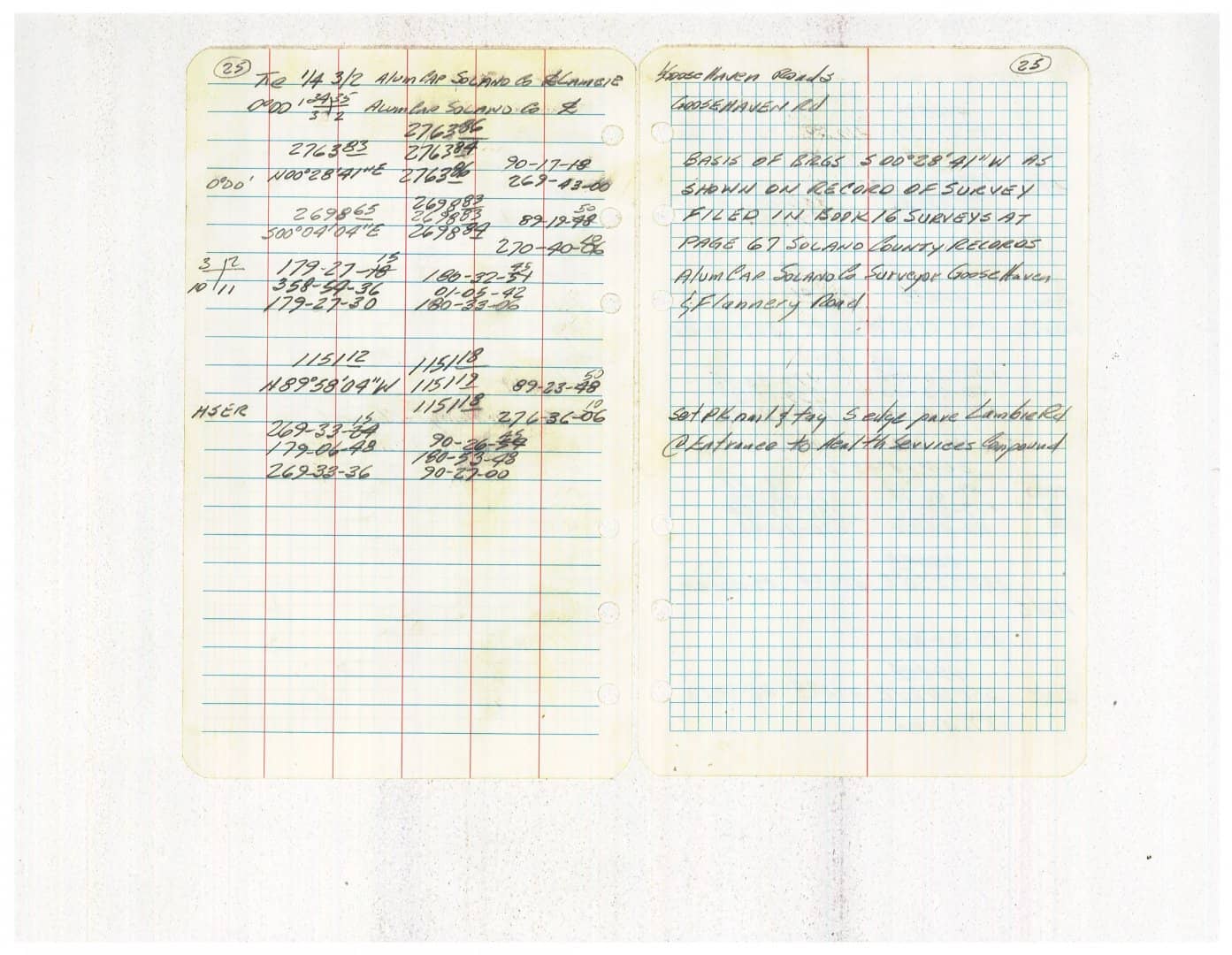

Left side of the book: Volume/page, Brief description of the tract and where it is located, then, from the bottom up, if conventional, traverse points, and all angles to traverse points and any corners set or found. Other side ties such as nails and their distances to fences do not need to have those angles recorded. All critical mark ups and mark downs and any rod height changes at selected points.

Right side of the book: Volume/page, crew, date, weather, from the bottom up, and trying to fit the traverse coming up the page, the traverse points, fence ties from control points, or other points, and as comprehensive of a sketch of the area as possible.

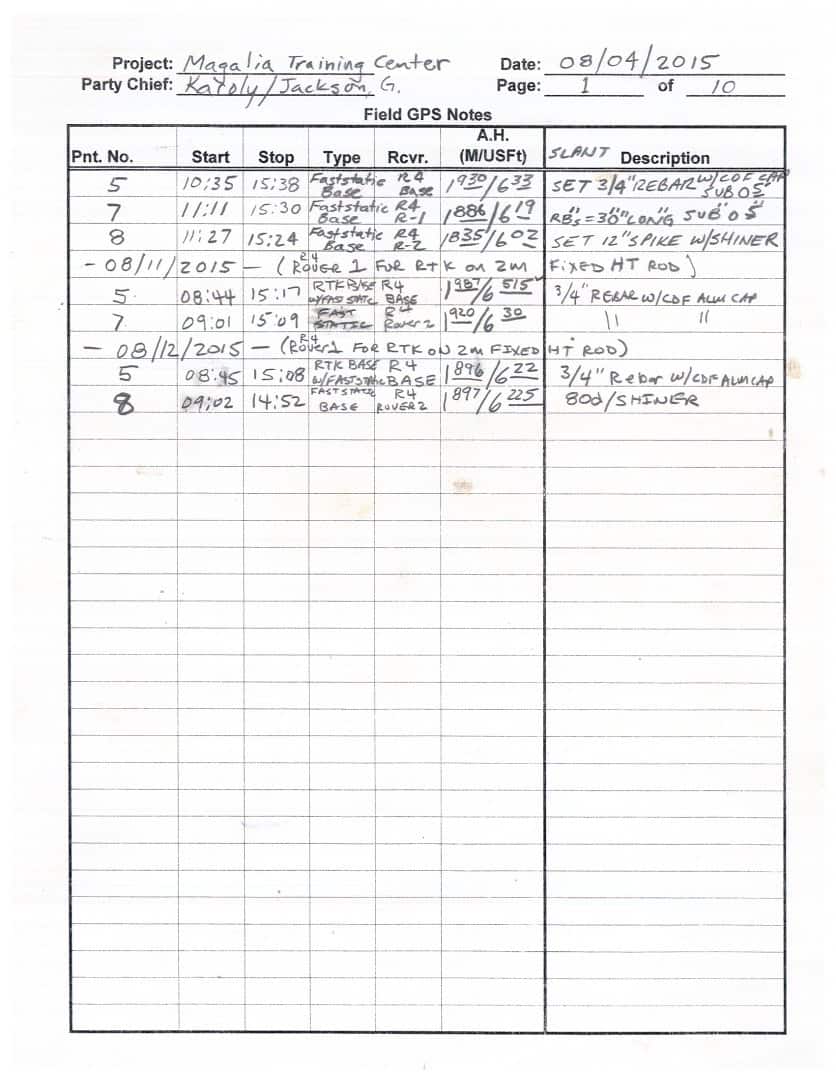

With GPS notes, the headings are the same, the sketch is the same, the descriptions of the points are the same, except there is no angular or distance data to record except between points shot that can be taped or other fence tie distances.

"...however if your computer crashes who is to say you really did turn 90å¡ and stake....."

That's a spurious argument. Your digital project data must always be properly organized and backed up. The raw data file will record what you actually did, not what you intended to do and mistakenly wrote down.

Locally, much of the work we do staking wise is not done with a data collector. If the staking must be done with a data collector then what is done is recorded, i.e. traversing in a wooded lot rather than turning angles from the center line and occupying the hubs/nails and turning 90å¡. Written checks to points from the hubs is more of a check than just "check the raw data..." I suppose my argument could be seen as spurious one, but if the I-man holds the angle in the gun and shoots the distance while being .20 off the prism and the collector records it as a perfect shot then your crew has just set a point off while being recorded as perfect. The raw data shows that you "actually" put it in the correct position, and you are now mistakenly being sued for .20 because the contractor, "Put it right where the surveyor did" and took photos. Recorded information digitally and manually both rely heavily on an honest crew and good math. I suppose now that field notes from the 1800's would be ruled out in court over modern raw data?

The ways of the screwup are many, and varied. I mainly challenge your "what if the computer crashes" argument. Proper procedures anticipate that eventuality.

Kris Morgan, post: 344800, member: 29 wrote: All of our field notes include the following

Left side of the book: Volume/page, Brief description of the tract and where it is located, then, from the bottom up, if conventional, traverse points, and all angles to traverse points and any corners set or found. Other side ties such as nails and their distances to fences do not need to have those angles recorded. All critical mark ups and mark downs and any rod height changes at selected points.Right side of the book: Volume/page, crew, date, weather, from the bottom up, and trying to fit the traverse coming up the page, the traverse points, fence ties from control points, or other points, and as comprehensive of a sketch of the area as possible.

With GPS notes, the headings are the same, the sketch is the same, the descriptions of the points are the same, except there is no angular or distance data to record except between points shot that can be taped or other fence tie distances.

These are the types of notes I'd like to follow, and therefore are the model I envision following if it's left to me to write my notes based on personal preference. I'm curious about the GPS notes you mentioned though, do you find it extraneous to calculate angles you'd otherwise measure with conventional methods and show them in your notes? I know it creates extra hassle, and I wonder if it's worth the extra time to show those calculations, or if you'd consider it more misleading as to how the measurement was gathered. Also, if you were calculating a point, whether it's a curve, corner you're setting, or anything else you may encounter, do you show your computations in a field book or allow the digital record from the data collector to be proof of how you computed something?

I would say they're less important than they were years ago, but there is still a lot of stuff that can be very helpful to write/draw in the fieldbook.

Personally, I take a lot of photos and everything, but sketches are better a lot of times. I measure buildings and other features and draw a detailed sketch in the fieldbook. This is especially important for measurements that haven't been directly surveyed in with the instruments.

Also, a quick sketch of the boundary information recovered, definitions of abbreviations, and descriptions of monuments go in there as well. I do not write down the raw data measurements as they used to. That stuff gets recorded in the raw data on the data collector and can be printed out. To me it doesn't seem like a smart use of my time duplicating that in the book when there is plenty of other information that needs to go in there.

When I worked with multiple crews I used to write down the coordinates of the control I set in the book so the next guy would have it if he didn't get it in the digital file for some reason.

Oregon's Department of Transportation has put together a document with some pretty good examples.

I'm a big believer in doing a control sketch in my notes, not necessarily to scale, if the survey borders on complicated. The main reason for this is that it forces me to take the time to really think about everything going on as I take the time to make the sketch. One of my older mentors that I took over for when he retired was a master at this, everything to scale and just a pleasure to look at and put all of the information in the notes into perspective. Couple weeks ago I got a call about a survey I did in 2012. Homeowner knew a fair amount about surveying and had run his own traverse, called up claiming I'd screwed up and we were encroaching with some of our facilities onto his property. Thankfully I had a good sketch in my notes of exactly what I'd done and how I came about my determination of where the lines were so I was able to send him a copy and he was able to immediately make sense out it and grudgingly admitted his conclusion was incorrect.

I don't subtend the bearings between GPS pairs unless I have to, and then, I write it in the book so it's not an issue. If I compute it with the GPS notes, it's in the book in some way, shape, form, or fashion, just so I can remember what the hell I did and why I did it. 🙂

As I read this thread I'm glancing at book number 2068 on my desk...

At bare minimum we require job #, job description, crew, book number, date, page number, and weather conditions in the header - typically job info and date on the left page, crew, book info, and weather on the right.

On the left page we require, at minimum, the control and QC point info and the HI / HT. The only time you need to record the HI / HT is when it changes, but make very sure that you do that. We usually record point number, feature code, and remarks on the left page as well.

On the right page we require a sketch, or a reference to the page number with the pertinent sketch. On linear jobs like pipelines the alignment runs from the bottom of the page to the top, with a north arrow to indicate the orientation. On topos the sketch is generally oriented to the north unless there are prominent geographic features that make sense to have aligned with the page.

We also require a surveyor's daily report - this is the place to record conversations with clients, property owners, etc.; changes in scope; moving from one job to another; AOCs - anything that might get called into question regarding the who, where, what, and why of the crew's activities for the day.

Of course, some party chiefs are better at all this than others.