Rankin_File, post: 379009, member: 101 wrote: I am always amazed at how well Kent's stamping looks

It's the punch mark. The lettering can just run all over the place unless you have a punch mark to hold it in place.

Oh, here's another photo from that project. The stones definitely appear to be the remains of an old mound, but aren't mentioned in any of the records of surveys made in the vicinity between 1835 and the present.

Considering what the rest of the corner mounds look like, I'd say it is most likely a line mound, probably from the late 1870s when the Armand Welch Survey was partitioned among the Burleson heirs. A fellow named Benjamin C. Hardin was County Surveyor then, and that resembles the style of line mound he made, i.e. just several largish stones in an artificial-looking arrangement. The subject of how to choose the center of a somewhat scattered mound is an interesting topic, but not exactly relevant here since the mound was just secondary evidence of where a line had probably been run in the 19th century.

Kent McMillan, post: 379102, member: 3 wrote: Oh, here's another photo from that project. The stones definitely appear to be the remains of an old mound, but aren't mentioned in any of the records of surveys made in the vicinity between 1835 and the present.

Considering what the rest of the corner mounds look like, I'd say it is most likely a line mound, probably from the late 1870s when the Armand Welch Survey was partitioned among the Burleson heirs. A fellow named Benjamin C. Hardin was County Surveyor then, and that resembles the style of line mound he made, i.e. just several largish stones in an artificial-looking arrangement. The subject of how to choose the center of a somewhat scattered mound is an interesting topic, but not exactly relevant here since the mound was just secondary evidence of where a line had probably been run in the 19th century.

Was the bovine skull already there, or did you place it there for effect?

Kent McMillan, post: 379102, member: 3 wrote: Oh, here's another photo from that project. The stones definitely appear to be the remains of an old mound, but aren't mentioned in any of the records of surveys made in the vicinity between 1835 and the present.

hello Kent,

I'm looking to learn something here, and perhaps some others will too. It seems a lot of marks you post pictures of, are buried. In the rural areas I survey, based on the marks I find, a majority of them are covered by less earth than I reckon they were when placed. Erosion (or mechanical movement of soil away) seems to be more the norm then deposition. What seems to be at work in Texas? Is it my confirmation bias? Is it a result of soil types? (lack of) weather? site specific? Is it an 'always dig' policy? how's the strike rate for marks as old as those you have shown?

The many times I have dug at reliably calculated corners around my area have mostly turned up nothing, and I think there's a good chance that farming activities have put paid to many of the marks. I'd be like to hear your opinions on when/where to dig/not dig, or anything you'd consider worthwhile to pass on. This just isn't the kind of thing that any of the surveyors i've trained under have had anything to say about.

Wind erosion in the Southwest is the norm. It taketh away and it addeth thereto. Not just in inches, but in feet.

Alan Cook, post: 379113, member: 43 wrote: Was the bovine skull already there, or did you place it there for effect?

A little of both. It was about thirty feet North of the remains of the mound, but looked much better in the photo. :>

Conrad, post: 379118, member: 6642 wrote: I'm looking to learn something here, and perhaps some others will too. It seems a lot of marks you post pictures of, are buried. In the rural areas I survey, based on the marks I find, a majority of them are covered by less earth than I reckon they were when placed. Erosion (or mechanical movement of soil away) seems to be more the norm then deposition. What seems to be at work in Texas? Is it my confirmation bias? Is it a result of soil types? (lack of) weather? site specific? Is it an 'always dig' policy? how's the strike rate for marks as old as those you have shown?

That entire project fell in an area that in the period before 1881 was grassland prairie. After that, when the railroad arrived, the large tracts that had been used as pasture for cattle ranching were broken up and sold as farms. In that particular area, most of the new farmers were immigrants from Germany who grew cotton on their lands. Cotton farming required tillage and that mean that the black clayey topsoil got moved around by water and wind (mostly by water) with areas in which the native grasses remained receiving some of the displaced soil. Contour plowing and other soil conservation practices were not followed in the 19th century that I'm aware of.

Several of the mounds fell alongside roads which were originally just graded dirt. Gravel pavements came later. The processes by which surface runoff washed soil particles into the native grasses along the shoulders can be seen also in how much lower the low strands of some very old 5-strand barbed wire fences are now than they would have originally been strung. That is, the soil level has risen to the level of that wire or above it.

In that area, unless a rock mound falls in an are that has obviously been disturbed by construction, I would ordinarily expect that the odds are good that it remains in place, if difficult to find. The quality of the chaining in the original surveys made between about 1835 and the 1880s was not particularly spectacular, so using the record distances to calculate search coordinates may often put one within only 30 - 50 ft. (or worse) of the actual location of the corner. Fortunately, the directions of lines are generally more predictable, although only relative to the "North" direction to which the surveyor adjusted his compass. So what one ends up calculating are search strips that may be, say 7 ft. wide and 30 ft. long.

For buried stones and stone mounds, a tee-handled probe is the tool of choice. I prefer a stouter one for the clay soils. It is pretty much a waste of time to search by other means unless one has a modern recovery note that narrows the position to a manageable radius. A trowel and whisk broom are the tools of choice for cleaning up the mound to actually see its outline and configuration.

The organization of the search is the key to finding things, but even an efficient search will take a good bit of time when there are no modern recovery records. I usually try to identify the corner with the smallest search area and begin from there. In this case, Corner No. 245 on the old Spanish highway from San Antonio to Nacogdoches was the main candidate. Since a survey in about 1881 had provided a survey tie from another corner about 1.14 miles away along the same old road that I thought I'd narrowed to an area of about 15 ft.

The 1854 surveyor gave a distance call to a waterway with well-defined banks about 400 ft. away from Corner No. 429. So that provided another good clue that limited the search radius quite a bit. I'm sure that the Theory of Search can be formalized to choose the schemes with the greatest probability of being the most time efficient, but in my experience there are almost always unexpected elements that would be difficult to model.

For example, the 1854 surveyor's work consisted of locating some land grants on top of a grant that had been made in the 1830s under Mexican sovereignty, but to which title had never been perfected by filing the title documents at the General Land Office as the law required (as best I can recall without cheating and actually looking at the file). The 1854 surveyor's task was to locate that phantom survey and to work within its boundaries. How exactly he attempted to do that is an open question, but it is entirely possible that short cuts were taken that account for some of the irregularities in the work.

The many times I have dug at reliably calculated corners around my area have mostly turned up nothing, and I think there's a good chance that farming activities have put paid to many of the marks. I'd be like to hear your opinions on when/where to dig/not dig, or anything you'd consider worthwhile to pass on. This just isn't the kind of thing that any of the surveyors i've trained under have had anything to say about.

I would not spend time looking for old stone corners in a plowed field. The place to search for them would be in the pile of stones that the farmer has carried over to the nearest fence! :> Somewhere, I have a photo of just such a pile in which I found several old stones that had formerly marked various corners falling inside a cotton field. It was pleasant not to have to wonder whether I had somehow missed them in my search.

Conrad, post: 379118, member: 6642 wrote: Erosion (or mechanical movement of soil away) seems to be more the norm then deposition. What seems to be at work in Texas?

I should have mentioned an excellent example of how grassland will capture windblown soil particles that I ran across about twenty years ago when I was surveying a large tract of good pasture surrounded by cotton farms. The difference between the ground level of the farmed land and the grazing land was quite marked. "Yes, the farmers, like to donate their topsoil to us," the rancher said. The ground level of the pasture tract had obviously risen quite a bit since the 1950s judging by the depth at which survey markers placed then were buried many decades later.

I have heard of cases in southwest Kansas and western Oklahoma where it took a full-sized backhoe to reach the full depth to the original stone from the dust mound left in the 1930's. The stones did not blow away. Obviously, somewhere else the local elevation decreased.

Holy Cow, post: 379141, member: 50 wrote: The stones did not blow away.

[MEDIA=youtube]5u_hy3BR9UM[/MEDIA]

Only in California could something that weird actually happen. State law forbids such frolicking elsewhere.

Kent McMillan, post: 378924, member: 3 wrote: In this discussion of mapping, I assume that most surveyors would agree that it is often useful to exaggerate the relationships of some features plotted in order to clarify their relationship for the benefit of the viewer

Don't agree, I think exaggerations are confusing and especially to any non-surveyor that may happen to look at the map. If you need to exaggerate, you should probably be using a detail, or even another sheet at a smaller scale if needed.

roger_LS, post: 379173, member: 11550 wrote: Don't agree, I think exaggerations are confusing and especially to any non-surveyor that may happen to look at the map. If you need to exaggerate, you should probably be using a detail, or even another sheet at a smaller scale if needed.

The problem with that is that you end up with a map with a zillion details that really doesn't tell the story as effectively as could be done with one map. For example, in the situation shown above, the problem is that the strip is barely 34 varas (94.4 ft.) wide, but the distance from the SW line of the Westbrook Survey to the NE line of the Welch Survey is about 5322 varas (2.80 miles) So the 34 vara strip could not be represented as clearly as it could be on a map with scale exaggerations. Even drawing the strip separately, it's still a thing less than 100 ft. wide and nearly two miles long.

If the real value of a map is to show the overal pattern, exploding it into ten different sheets trades the big picture for the details that by themselves don't really tell the story as well. Naturally, an exaggerated scale diagram would not work for any purpose that required a scaled representation, but for the purposes of explanation and discussion, that would often not be the case.

Kent McMillan, post: 379174, member: 3 wrote: The problem with that is that you end up with a map with a zillion details that really doesn't tell the story as effectively as could be done with one map. For example, in the situation shown above, the problem is that the strip is barely 34 varas (94.4 ft.) wide, but the distance from the SW line of the Westbrook Survey to the NE line of the Welch Survey is about 5322 varas (2.80 miles) So the 34 vara strip could not be represented as clearly as it could be on a map with scale exaggerations. Even drawing the strip separately, it's still a thing less than 100 ft. wide and nearly two miles long.

If the real value of a map is to show the overal pattern, exploding it into ten different sheets trades the big picture for the details that by themselves don't really tell the story as well. Naturally, an exaggerated scale diagram would not work for any purpose that required a scaled representation, but for the purposes of explanation and discussion, that would often not be the case.

There may be very extreme situations where they would be appropriate, maybe this is one of them, I don't know. In my opinion, it should be an absolute last resort. And if they are used, seems to me there should be notes on the face of the map showing which areas have been exaggerated. Guess it depends on who the map is prepared for, if it's a surveyor, sure, they could figure it out. But if the viewer is anyone else, it's confusing.

[SARCASM] I figured that based on the sheer volume of BS spouted by certain Texans, digging for corners was just a given...[/SARCASM]

roger_LS, post: 379203, member: 11550 wrote: Guess it depends on who the map is prepared for, if it's a surveyor, sure, they could figure it out. But if the viewer is anyone else, it's confusing.

Take the common example of showing fences and survey markers that fall to one side of the boundary or another. If plotted to scale, the only clue that the feature isn't exactly on the line is some annotation. If plotted with scale exaggeration, the linework itself immediately tells the viewer what the situation is (with the annotation providing any dimension, of course.

Likewise, the common situation of multiple markers in place in the vicinity of a corner. Why clutter a map with an inset when simply indicating the surplus markers, exaggerating scale as necessary for clarity and giving the ties to them in the marker descriptions does the trick perfectly well?

Kent McMillan, post: 379210, member: 3 wrote: Take the common example of showing fences and survey markers that fall to one side of the boundary or another. If plotted to scale, the only clue that the feature isn't exactly on the line is some annotation. If plotted with scale exaggeration, the linework itself immediately tells the viewer what the situation is (with the annotation providing any dimension, of course.

Likewise, the common situation of multiple markers in place in the vicinity of a corner. Why clutter a map with an inset when simply indicating the surplus markers, exaggerating scale as necessary for clarity and giving the ties to them in the marker descriptions does the trick perfectly well?

It's up to you. If there was a serious problem with a fence, I'd probably take the time to add a detail or even an extra sheet to show it. There's nothing like a scaled drawing to tell the story rather than a schematic like an electrician might put together.

Rankin_File, post: 379209, member: 101 wrote: I figured that based on the sheer volume of BS spouted by certain Texans, digging for corners was just a given.

No, I'm pretty sure that you have the PLSS in mind there, with several railroad spikes at the road intersection to guide the excavation. In Texas, a surveyor could wear out five shovels before he or she ever found some 19th-century survey markers. A probe is definitely the way to go for efficient search, particularly in blackland prairie where stone mounds do not naturally occur and large stones are rare.

roger_LS, post: 379217, member: 11550 wrote: It's up to you. If there was a serious problem with a fence, I'd probably take the time to add a detail or even an extra sheet to show it. There's nothing like a scaled drawing to tell the story rather than a schematic like an electrician might put together.

Scale drawings probably work better for very small parcels drawn at large scales like 1:240 than they do in the case of surveys covering larger tracts at scales smaller than 1:2400. It's really just a problem in communication, i.e. figuring out how to most efficiently communicate some finding to the expected viewer/user of the map, and invariably exaggeration of scale works much better than lots of details that provide more of a map "kit" than a map.

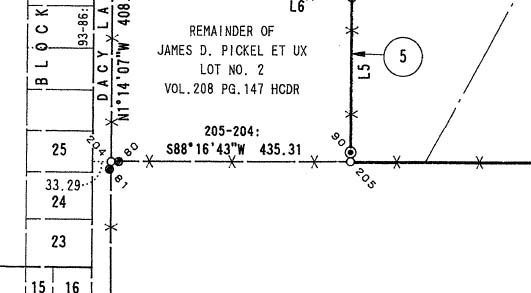

For example, here's a detail of a map compiled at a scale of 1:2400. Note how readily one sees that in the vicinity of Rod and Cap No. 204 there are two other markers. The descriptions are keyed to the point i.d. nos. and provide the ties.

Similarly for 90-205, which are 0.77 ft. apart.