I've been working on a research project in an older part of Houston in which one of the questions is when the Houston City Engineer placed various markers on certain lines known in Houston as "reference lines". There are some areas where the reference lines supposedly marking where a City Engineer may have *thought* the rights-of-way of various streets to be in the 1920's are at large variance with where prior City Engineers evidently thought the rights-of-way to be. Not unsurprisingly, one bit of evidence of that is where street pavements were constructed before the 1920's.

Anyway, in the course of digging up the history of street paving, to document that various of the streets in question were actually originally paved in 1904 and 1905, well before the later surveys that supposedly "fixed" the locations of the streets in neighborhoods that were already nearly completely built up, I found this map showing every paved street that existed in Houston as of 1910. It shows a variety of paving methods, from bois d'arc blocks, to brick, oystershell, gravel, macadam, asphalt, and bitulithic. If you like dirt roads, you'd have been in luck in 1910 because most of them were.

For anyone who is interested in the progress of paving in Houston after 1902, here are some links. The City Engineer's annual reports from this period are interesting in that the basic choice of paving materials and design of drainage and utility improvements were still a work in progress.

"Annual message of Mayor of the City of Houston and annual reports of city officers, 1902"; Pg. 37

https://archive.org/details/annualmessageofm1902city

"Annual Message of A.L. Jackson, Mayor of the City of Houston and Annual Reports of City Officers for the Year Ending December 31, 1904" Pg.78

https://archive.org/details/annualmessageofm1904city

"Annual Message of H.B. Rice, Mayor of the City of Houston and Annual Reports of City Officers For the Year ending February 28, 1906", Pg.76

https://ia802601.us.archive.org/10/items/annualmessageofm1906city/annualmessageofm1906city.pdf

"Annual Message of H.B. Rice, Mayor of the City of Houston and Annual Reports of City Officers For the Year ending February 28, 1911", Pg.117

https://archive.org/details/annualmessageofm1910city

"Mayor's Annual Message and Department Reports For the Year Ending February 29, 1912, W.H. Coyle & Co., Stationers and Printers, Houston, Texas", Pg.87

https://archive.org/details/annualmessageofm1912city

One of the few references I've ever seen on a map for a "bitulithic" road. Although we generally call it "asphalt pavement" nowadays, it eventually changed the entire pavement industry.

From reference material:

In 1901 and 1903, Frederick J. Warren was issued patents for the early ÛÏhot mixÛ paving materials. A typical mix contained about 6 percent ÛÏbituminous cementÛ and graded aggregate proportioned for low air voids. Essentially, the maximum aggregate size was 75 mm ranging down to dust. The concept was to produce a mix which could use a more ÛÏfluidÛ binder than used for sheet asphalt. This material became known as ÛÏBitulithic.Û

Warren's mix-design is not that different from what we use today. With a content of actual asphaltic cement (sticky messy ooze) being in the 5% to 7% range, the tar did not bleed or pool on warm days, one of the drawbacks of early bituminous road surface. And mixed with the proper sized aggregates, it hardens to become an actual asphaltic concrete pavement.

paden cash, post: 360511, member: 20 wrote: One of the few references I've ever seen on a map for a "bitulithic" road. Although we generally call it "asphalt pavement" nowadays, it eventually changed the entire pavement industry.

Yes, possibly the only road surface not represented in Houston in 1910 is the plank road. I wonder if there are still any bois d'arc block pavements hiding under an HMAC course somewhere within the limits of Houston.

Kent McMillan, post: 360512, member: 3 wrote: Yes, possibly the only road surface not represented in Houston in 1910 is the plank road. I wonder if there are still any bois d'arc block pavements hiding under an HMAC course somewhere within the limits of Houston.

There would have to be given the impossibly dense structural integrity of the mighty bois d'arc wood. I read not too long ago about a 12' diameter wooden timber plug found recently at the bottom of a channel off the Thames River near London during some dredging activity. It also had attached to it a large link section of chain....when they pulled it to the surface, the channel drained into a previously unknown masonry sewer that lead to the actual river. The "world's largest bath tub stopper" was determined to be made of oak timber and around 250 years old.

If oak can last at the bottom of the Thames for two and a half centuries, bois d'arc could easily stay undisturbed for a hundred or so years.

Kent McMillan, post: 360512, member: 3 wrote: I wonder if there are still any bois d'arc block pavements hiding under an HMAC course somewhere within the limits of Houston.

There are Bois d'arc stakes in place in Bowie County from that period that have probably been underwater from the Red River as much and infrequently as Houston has.

Bois d'arc is my favorite firewood. I would have never though to build a road out of it.

In Ohio, we refer to the tree as a hedgeapple. The fruit we call monkey brains.

Kent,

Interesting reading. Thank you for posting.

paden cash, post: 360511, member: 20 wrote: One of the few references I've ever seen on a map for a "bitulithic" road.

That same 1910 map may well show more different railroads than exist in an area that size anywhere else in the US. There is an amazing number of different lines noted on that map. It's easy to understand why the City of Houston has a steam locomotive on the city seal instead of a limo in a traffic jam.

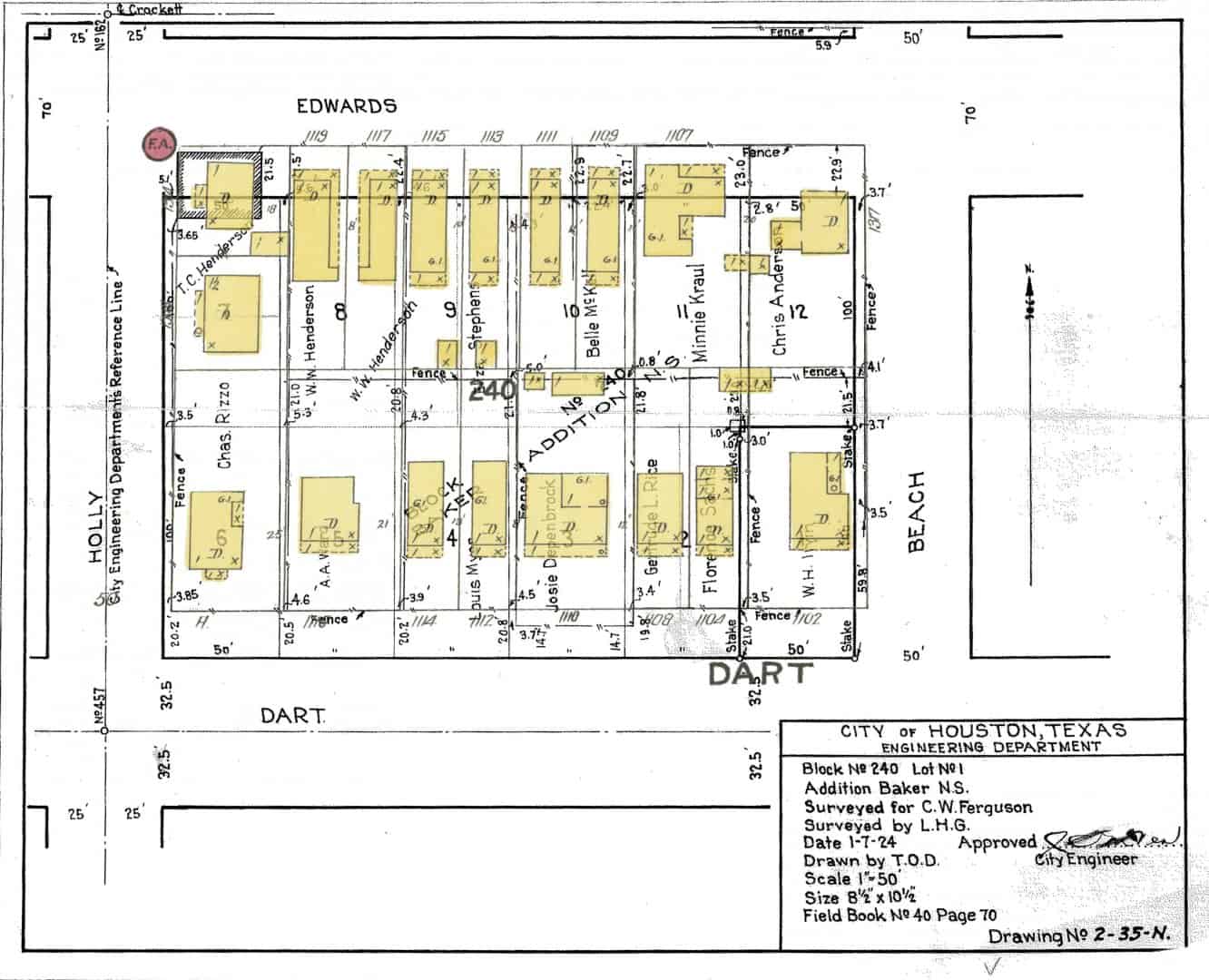

Oh, the map below is an example of what a poor job the Houston City Engineer's surveying staff did in some instances in the 1920's. It's a composite of a map of a survey made in 1924 by the surveying staff onto which I've overlaid the buildings (in yellow) as shown upon a 1907 Sanborn's Fire Insurance Map (since the city surveyors neglected evidently to mention the fact that their location of the South line of Edwards Street ran though every building in place on the North half of Block 240, some of which still exist in the identical position).

The City Engineer's map represented his theory as to the location of a certain block of 50 x 100 ft. lots originally laid out in the 1850's and mostly sold by the developer, a fellow named W.R. Baker, to various owners in the 1860s and 70s, but as located strictly by theoretical measurements from a reference line four blocks distant.

I wonder why you stated that they were oyster shell roads. Legend states 'shellÛª.

Most of the shell roads, drives, fill here were clam shells that were dredged or collected. This clam shell was used by the Native Americans as a food source and used in building mounds and middens in wetland areas etc... Dredging stopped in the late 1980Ûªs here for environmental reasons that led to the import of limestone gravel or the use of local river gravel. Everyone can remember the barges dredging on the lake here.

Cobblestone and granite setts were used also in New Oceans. I think that they were used as ballast and brought to the city by ships and barges. I think most colonial port cities have cobblestone and/or granite block to this reason. I havegranite blocks on my garden from the streets of the city.

New Orleans had plank roads. But the clam shell was used extensively. There is always a sigh of grief when you have to start digging for a monument and you encounter clam shell. Impervious to the spade and sharpshooter shovel signaling it is time to fetch the pic-axe.

Oyster shells were used at times for fill when the shells could be collected and transported with ease. Some building lots used oyster if they were available.

I always thought that the clam shell roads brought an aesthetic to the landscape for some reason.

John Evers, post: 360533, member: 467 wrote: Bois d'arc is my favorite firewood. I would have never though to build a road out of it.

In Ohio, we refer to the tree as a hedgeapple. The fruit we call monkey brains.

That's unique...we call the fruit a hedge apple and the tree a 'boe-dark'.

And the fruit is actually good for something..getting rid of ants. Put one on top of an ant pile and there won't be anymore ants in a few days, honest.

Robert Hill, post: 360556, member: 378 wrote: I wonder why you stated that they were oyster shell roads.

The only references that I've found in Houston are to oyster shells used in paving. I assumed that the source of the shell was from dredging rather than from paleo-Indian debris mounds. At any rate, the use of shell pavements seems to coincide with dredging activities in Galveston Bay and Buffalo Bayou.

One reference to a source for shell paving material in Houston ca. 1910 were the shell reefs of Dog Island and Shell Island near the mouth of the Colorado River, which apparently were predominantly of oyster shell.

paden cash, post: 360583, member: 20 wrote: That's unique...we call the fruit a hedge apple and the tree a 'boe-dark'.

And the fruit is actually good for something..getting rid of ants. Put one on top of an ant pile and there won't be anymore ants in a few days, honest.

Another twist; growing up we called the fruit a horse-apple. Like you, the tree was called a "boe-dark".

Kent McMillan, post: 360512, member: 3 wrote: Yes, possibly the only road surface not represented in Houston in 1910 is the plank road. I wonder if there are still any bois d'arc block pavements hiding under an HMAC course somewhere within the limits of Houston.

Kent, the oldest paving I have seen is in Freedman's town, just south of where you're at. Brick supposedly from the 1800's. Where the asphalt has been worn down, you can see 'em, the old rails are there, too..

Kent McMillan, post: 360878, member: 3 wrote: The only references that I've found in Houston are to oyster shells used in paving. I assumed that the source of the shell was from dredging rather than from paleo-Indian debris mounds. At any rate, the use of shell pavements seems to coincide with dredging activities in Galveston Bay and Buffalo Bayou.

One reference to a source for shell paving material in Houston ca. 1910 were the shell reefs of Dog Island and Shell Island near the mouth of the Colorado River, which apparently were predominantly of oyster shell.

http://wgno.com/2016/03/03/someone-filled-maple-street-potholes-with-oyster-shells/